Famed design rule breaker David Carson once said, “Graphic design will save the world right after rock n roll does” which does a decent enough job at outlining my position.

It’s the curse of many professions to think their slice of the whole is the key. Everyone in the Silo believes their job is the thing keeping humanity alive, no matter how trivial. The entire VC-fueled AI apparatus will tell you AGI will save the world (for the low price of unlimited funding, barely-constrained power in the hands of the few, and maybe “the whole structure of society [being] up for debate and reconfiguration”.) We’ve all got a bad case of main character energy.

I don’t know if it’s the winter doldrums, middle age, or the unending parade of novel sicknesses, natural disasters, and cultural upheavals, but I’m not feeling optimistic about design saving the world lately.

Design as the marketing arm of capitalism

I’ve been a professional designer for more than half my life. Hundreds of websites, thousands of logos, and more drawings, album and book jackets, presentation decks, user flows, t-shirts, brand guidelines, and posters than I can quantify. But most of that stuff is gone. Poofed. Digital ghosts, forgotten artifacts from dead companies, poly-cotton blends hanging on thrift store hangers. Not exactly the stuff of legacy.

As far as most design professionals go, I’d wager I’m not unique in this. When you opt for a career in the trendy and ephemeral, you reap what you sow.

The good news is, I have a job (or at least an amalgamation of short-term gigs that make a reasonable facsimile of a job). The bad news is, my job is capitalism. As my friend Hudlow lamented regarding life in the Star Wars universe, “only the Empire hires designers.” Fascism is on the rise, and centralized autocracy craves brand consistency. I remain employable, at least until the droids replace me.

Once upon a time…

From 2009–2010, while I was helping to build an in-house design team at the fast-growing non-profit where I worked, I began getting recruiter emails and calls from Silicon Valley tech companies, including Facebook.

Facebook was starting to heavily recruit design talent, including many folks I looked up to. It was flattering. I met some great folks I still keep in touch with. But the Blankenships were young in our marriage, just starting to feel settled in South Carolina, and I thought I had something to prove about the value of design, how it could impact a local community, and the good we could do if you stuck around for awhile, so in my naiveté I turned those offers down without much consideration.

Staying on the East Coast is one of those Sliding Doors moments where it’s easier to see diverging paths and timelines in your own life.

I stubbornly stayed in that non-profit job for another six years, long past when I should have, before they finally politely asked me to leave. I probably stagnated in my skills and career trajectory, at a time when the relatively new disciplines around digital product design were growing by leaps and bounds. Meanwhile most of that era of recruiting class went on to well-connected careers and, if they played their cards right, no small amount of fortune when Facebook IPO-ed in mid-2012.

This isn’t about regret — I’m honestly not sure how our marriage would’ve weathered tech company + Bay Area commute hours, or how well my character (or the unearned designer chip on my shoulder) would’ve done that environment. We traded money and opportunity for relational stability and the belief we could do the most good where we were, and made measured decisions with the information we had at the time. Hindsight benefits from perfect information.

So did it work?

I tell you that story to set up the context we’re facing in our rapidly growing city, as gentrification is nipping at the heels of my neighborhood, and every month brings news of another luxury townhome project dotting the landscape: do I have the right tools to help my neighbors?

I’ve spent 22 years building a suite of design skills — articulating thoughts, understanding clients and markets, selling concepts, and pushing pixels — and made a decent living, too. Which helps me, and by extension my family, and the clients I work with. But can any of that help my neighbors stay in their homes? And does any of it help me be a good neighbor both generally and specifically?

This where the sliding doors thing comes into play: what’s better, community organizing a spectacularly-branded campaign for more affordable housing (or) having a IPO nest egg that could help me buyout the landlord who owns 35 of the ~700 homes in my my neighborhood (that’s 5% of the housing supply!), and then offering them for below market rate rents? One of those seems real, and one of them seems performative, at best.

My presentation skills mean I can succinctly give a reporter a good soundbite, or make a compelling point in front of city council, but the folks who own the real estate and leverage those assets to develop them are driving the conversation before I ever touch a microphone. Which is a big capitalism bummer, but is also the context I have to design into and around.

Where to next, designer man?

I recently told a friend that if a young, smart person wanted to make an impact on their community, I’d have a hard time counseling them to pursue graphic design — I’d recommend law school if they want help build something that can last. But as pessimistic as I might be about design right now (which, again, might just be the Winter talking) I remain optimistic about people.

When it comes to community things in my city, I care less about the brand identity of the neighborhood than I do about the actual neighborhood. I want my neighbors to meet each other. I want our kids play in the front yard while we exchange plants and talk about traffic. I want to be sure the kind retiree on the corner who always whistles as he drives by isn’t lonely. I want to care about people.

Design, yes. But design in service of building community.

Up next

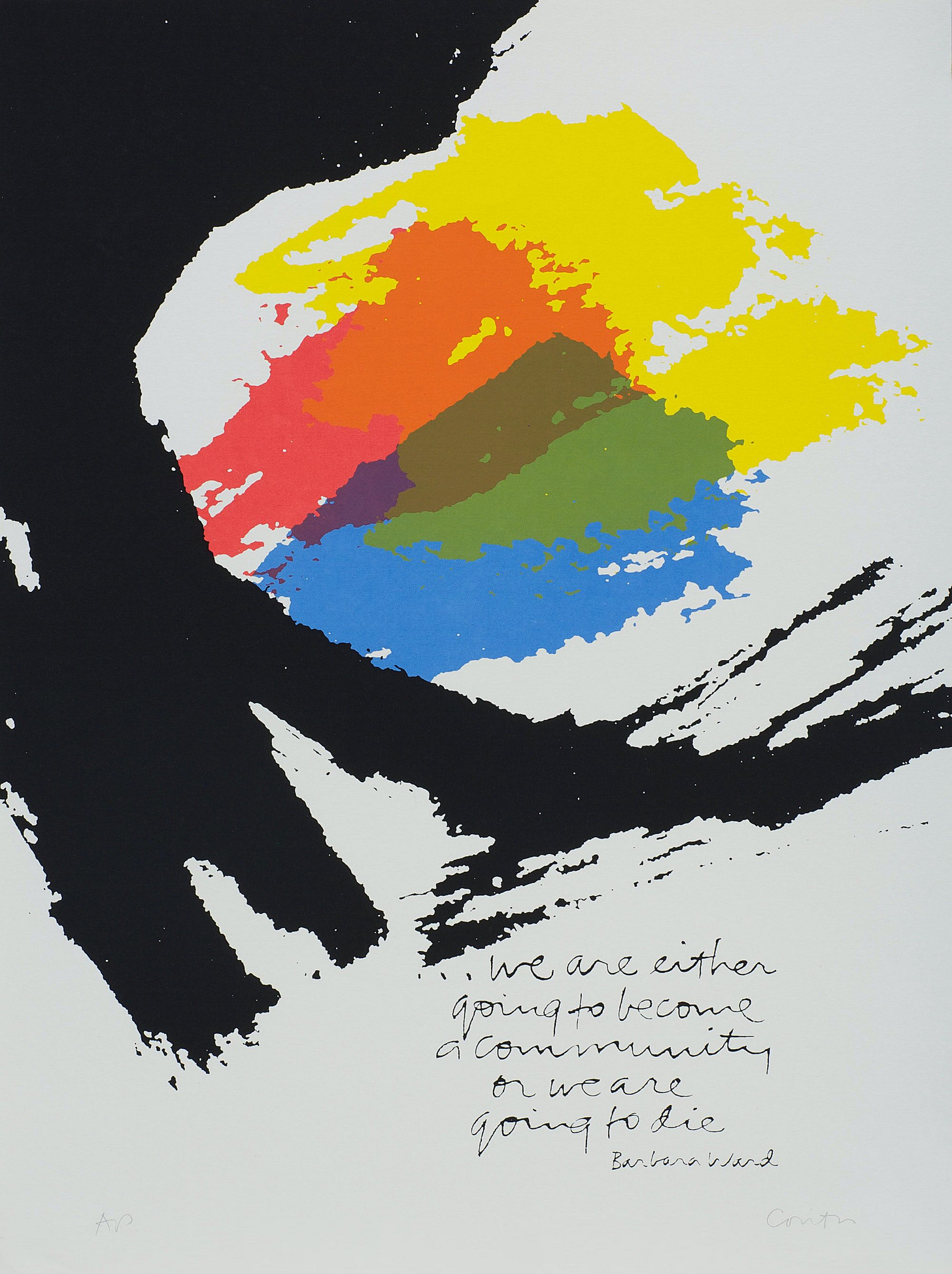

Barbara Ward said, “We are either going to become a community, or we are going to die.”

We’re working on a new project called Poets Live to organize and share live poetry events in Greenville, including the poets’ open mic we’ve been hosting at the occasional coffeeshop or bar. And maybe that seems silly, considering the world around us, but I believe art matters because people need it. (There’s a great interview with Ethan Hawke where he talks about poetry that’s absolutely worth your time.)

And sure, I’m a designer — I made little a logo and I’m working on a makeshift website for Poets Live. But the point isn’t the design; the point is community. We need more gathering, reasons to get people out in public, sharing work, and feeling seen and encouraged.

I’m glad I have the skills to help endeavors like this with an easily-recognizable identity. But it’s in the same way I’m glad I can play guitar, or frame a house, or efficiently cut a bell pepper. Useful stuff to know; horrible things to build a personality around. Certainly not enough to save the world. But plenty to build a rich life in community, alongside other people trying to make things a little better every day.

Design won’t change the world. But people will.